Wirecard: Another Fintech Fraud

By Violeta Perea Rubio

Wirecard filed for insolvency on June 25th 2020. The act is the culmination of a long fraud and a failure of regulatory mechanisms to uphold financial ethics. The fraud came to light when Wirecard was unable to justify €1.9 billion in its accounts. Wirecard later revealed the money “probably didn’t exist”, owning up to lying and fraud (Chanjaroen). Wirecard’s key ethical failure is its prolonged lying and fraud, spanning over two decades. As a result, an ethical analysis includes not only the Wirecard management, but a wider range of moral agents, from external German regulators BaFin, to internal auditors Ernst & Young (EY) complicit through their negligence. The analysis raises ethical questions around regulatory capture, conflict of interest, and financial transparency, collateral to the central consideration of Wirecard’s lying and fraud.

The Rise and Fall of Wirecard

Founded in 1999 in Munich (Germany), primarily as a provider of financial services to the gambling and pornography industries at the close of the dotcom boom, Wirecard expanded steadily in the early 2000s in the online payment transaction sector. In 2006, CEO Markus Braun pulled Wirecard into banking through the acquisition of XCOM AG. This allowed Wire Card AG to enter the debit and credit card issuing business, gaining a universal banking licence (“Wire Card AG acquire XCOM”). In entering these markets, Wirecard obtained licenses from Visa and Mastercard. In the early 2000s, Wirecard became a hybrid and complex company functioning across multiple sectors.

Perhaps its early years as a provider to the gambling and pornography industries should have raised red flags on the ethics of Wirecard. Islamic finance, which incorporates Shariah Law in its financial ethics and legislation, holds that “all economic activity should aim at human well-being, which includes justice, equality harmony, moderation and a balance of material and spiritual needs” (Boatright, p.14). In upholding the values inscribed in the Qur’an, one of the key tenets of Islamic finance is the avoidance of haram activities, such as drugs, gambling and pornography. Therefore, Wirecard’s early provision of financial services to these industries would be seen as immoral under Islamic finance.

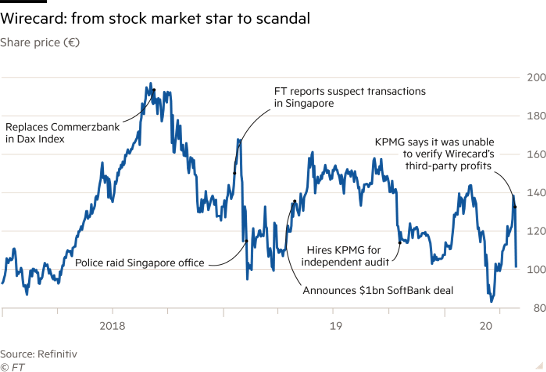

In 2008, Wirecard’s accounting integrity was first challenged by a German investors’ association SdK. The saga concluded with the sentencing of SdK officials Tobias Bosler and Markus Straub by Munich prosecutors for short selling and market manipulation in 2011 (Boerse.ARD.de). Thus, began a pattern of prioritizing the crackdown on unethical and illegal short sellers at the expense of investigations into Wirecard’s accounting practices by regulators. The pattern repeated in 2016 and 2019. The 2008 scandal included accusations against Wirecard of non-transparent reporting, suspicious M&A activities, aggressive profit accounting, and rumours of money laundering associated with illegal US online gambling. After this scandal, EY became Wirecard’s auditor.

Wirecard’s share price quickly recovered from the 2008 scandal as the group grew rapidly in the proceeding decade. In 2010, Jan Marsalek was appointed Chief Operations Officer (COO). By 2010 the majority of the key players involved in the final 2020 scandal were central in making the ethical decisions regarding Wirecard, namely Marsalek, Braun and EY. External governmental regulators ought to have become increasingly involved as Wirecard grew and topped the Frankfurt stock market.

Aggressive International Expansion

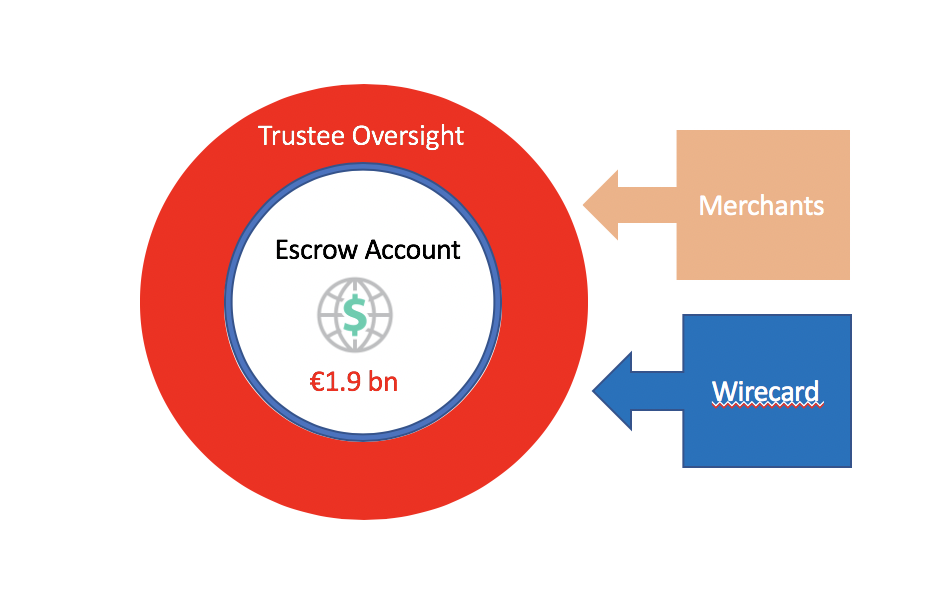

After 2010, Wirecard began an aggressive international expansion and growth, with bases in Germany, Dublin and Dubai, raising half a billion euros from shareholders (McCrum, “Timeline”). Expansion into Asia was achieved through complicated third-party deals and escrow accounts, particularly in Dubai, Singapore, and the Philippines, all of which later became the loci of Wirecard’s accounting irregularities. An escrow account is a financial instrument whereby a third party holds and regulates a transaction between two other parties on their behalf, holding the assets until the transaction is completed. Wirecard used these escrow accounts to explain accounting irregularities to auditors, arguing missing money was held in such accounts.

The rapid expansion of Wirecard into a multi-national company through acquisitions of third-party companies, such as Singapore-based E-Credit Plus PTE Ltd or Ashazi services in Bahrain, led to questions over Wirecard’s unique and dubious expansion tactics. Indeed, The Financial Times suggests these international deals raised doubts over the value of €670 millions of intangible assets on the balance sheet as early as in 2011 (McCrum, “The Strange Case of Ashazi”).

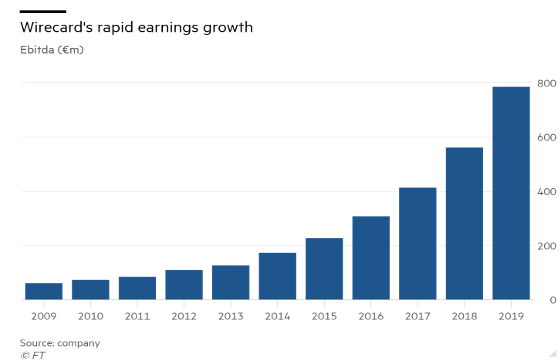

Nevertheless, despite the suspicious expansion, there was little regulation of Wirecard, with auditors EY signing off seemingly unsatisfactory balance sheets for the rest of the decade. In 2010, Wirecard’s net earnings reportedly grew by 16% (See Figure 1), beginning the company’s exponential earnings growth (Gavin). By 2013, Goldman Sachs’ forecast for Wirecard stock gains led to an immediate 5.2% jump in share prices (Morgan).

Financial Times vs Wirecard: The Beginning of a Feud

Headed by investigative journalist Dan McCrum, The Financial Times began publishing a series on Wirecard’s accounting irregularities in 2015 (FT Alphaville, House of Wirecard), prompting a feud between the FT and Wirecard which lasted for 5 years. In the series, the FT claimed there was a €250 million hole in Wirecard’s balance sheet (McCrum, “House of Wirecard”).

In October that year, J Capital Research, a US and Hong Kong independent research group, published a report that recommended shorting Wirecard stocks. In the report, JCap raised doubts about Wirecard’s Asian partner companies, stating:

“Having found little evidence that Wirecard has any volume of business, we visited five of the subsidiaries in Southeast Asia. Only one of the premises had a reasonably credible presence, and even that one appeared much smaller than disclosures would suggest. At two of the listed locations we could find no company at all, although there were unrelated companies with similar names” (McCrum, “JCap on Wirecard”).

Again, suspicion was raised over Wirecard’s Asian expansion. According to the report, JCap was unable to locate the third-party offices in either Cambodia or Laos, with the ones in Vietnam and Singapore having “no capacity for providing [the] services” Wirecard suggested it provided. In response, Wirecard denied all of JCap’s claims, suggesting it failed to understand Wirecard’s business model and its report was “ultimately misinformation and incorrect” (Ibid.). Wirecard emphasised success in its Asian expansion, quoting that “around 25% of Wirecard’s transaction volume relate from merchants headquartered outside of Europe.” The JCap report concluded “We think that fictional assets in Asia may be hiding the uncomfortable truth that there is no profit”. With hindsight, JCap’s report pre-empts the future discovery of the €1.9 billion ‘hole’ in Wirecard’s balance sheet, which points to fraudulent methods in accounting for Wirecard’s Asian assets.

Despite JCap’s report and The Financial Times’ multiple case studies and investigations, no significant regulatory or audit inquiry was undertaken, exhibiting EY and BaFin’s negligence of their duty to uphold financial transparency.

Regulators Blinded by Fear of Short Sellers: Zatarra Report

From 2016 onward Wirecard faced an increasing number of ‘attacks’ that accused it of accounting manipulation and fraud. The Zatarra report, published anonymously through Twitter, accused Wirecard UK of money laundering in the US for illegal online gambling, among other claims of accounting irregularities and fraud. However, the anonymity of Zatarra and its unverifiability allowed these claims to be quickly dismissed by Wirecard, who accused the Zatarra report of market manipulation by short-sellers.

Short selling describes an investment strategy which speculates on the decline of the stock of a certain company. Short sellers ‘short’ the stock by selling shares with the intention of buying them back at a lower price in the future, making profit from the difference in price. Short-sellers therefore benefit if there is a decline in stock, which is counterintuitive as stock prices generally increase with time, making short-selling a risky strategy. Because of this risk, short-selling is often linked to accusations of market manipulation.

After the Zatarra report, Wirecard’s shares saw a short-lived 25% drop in price. CEO Markus Braun claimed all statements by Zatarra were false and “slanderous”, leading to an immediate surge of 8.9% (Stefan and Rach). This surge clearly demonstrated investors’ scepticism towards Zatarra and a misplaced trust in Wirecard.

This scepticism was shared by German regulators BaFin. From 2016 onward BaFin become a key player in the Wirecard scandal. BaFin is the abbreviation for the Federal Financial Supervisory Authority in Germany, an “autonomous public-law institution” subject to supervision by the German Ministry of Finance. In response to the Zatarra scandal, BaFin opened an investigation into Zatarra and potential short-sellers associated with it for market manipulation. Ironically, BaFin did not seriously investigate the claims made against Wirecard. Despite the sequence of similar accusations made against Wirecard by various individuals and organizations, Wirecard continued growing operations without in-depth regulatory investigation. Thus, auditor EY and regulator BaFin displayed fiduciary and regulatory negligence respectively.

The reasons why market manipulation and fraud are both unethical are similar. Both are unethical because they centre around lying, forsaking transparency and undermining commutative justice. BaFin’s prioritization of a crackdown on market manipulation over a crackdown on fraud creates an unfounded ethical hierarchy as both malpractices equally threaten transparency and fair play. The imbalance in treatment of both claims of misconduct suggests a parallel imbalance in loyalties in both BaFin and EY favouring Wirecard. Hence, the immoral fiduciary and regulatory negligence that allowed Wirecard to continue its fraudulent growth.

In 2018 Wirecard reached new heights as it entered the DAX 30 index of Germany’s top 30 companies overtaking Deutsche Bank in earnings (Figure 2). Wirecard was valued at over €21.1 billion euros in 2018 and became Germany’s pride and Europe’s greatest technology company (Smith).

This growth is owed in part to EY’s publication of a clean audit report for 2017, clearing allegations of accounting irregularities and regaining investor trust. It was later found in June 2020 that EY failed for more than 3 years to request account information from a Singapore bank to corroborate Wirecard’s claims that it held up to €1 billion in cash there (Kinder, Storbeck, Palma). Had EY checked these bank statements, as is standard procedure for auditors, much of the fraud discovered in June 2020 could have been revealed and prosecuted earlier.

Financial Times vs Wirecard: Final Attack

After years of close monitoring and investigation into Wirecard, Dan McCrum from The Financial Times published an article in late January 2019 accusing Wirecard of accounting irregularities, including “forgery and/or of falsification of accounts” and “cheating, criminal breach of trust, corruption and/or money laundering” (Palma and McCrum). These allegations primarily concerned practices in Singapore and the Asian market. The article highlights practices like ‘book-padding’, ‘round-tipping’ and back-dating. Though this ‘Project Tiger’ investigation primarily targeted Edo Kurniawan who ran the finance and accounting operations for Wirecard in Singapore, it implied similar fraudulent practices were endemic across the company.

The FT’s report led to an immediate drop in stock prices by 25% and erased $10 billion from its market value. The whistle-blower who presented the FT with the May 2018 ‘Project Tiger Summary’ document where the accusations were outlined, allegedly also sent the documents to BaFin in January 2019, according to the German finance minister. Nevertheless, after publication of the FT article, BaFin temporarily banned short-selling of Wirecard stock and began an investigation into short sellers and FT journalists. Wirecard sued the FT for defamatory claims and market manipulation, claiming there was collusion between the journalists and short-sellers. Wirecard also sued Singapore authorities undertaking the criminal investigation. At the same time, Wirecard hired an external audit by EY rival KPMG. Later, KPMG’s special audit revealed on April 28th 2020 it could not verify certain deals with third-party companies and found several “obstacles” in undertaking the audit.

Wirecard’s Threats and Intimidation

Wirecard is suspected of using intimidation tactics against journalists and other research groups shedding light on the company’s potential accounting irregularities. J Capital Research told The Financial Review it faced multiple threats after the publication of its report in 2015, with JCap founder Tim Murray stating: “It got really grubby – there was speculation about kidnap threats. We were hacked.” (Maley) Likewise, Dan McCrum experienced similar forms of intimidation, expressing this in an interview “you constantly think your emails are going to be hacked, or if you think people are following you. There was a period where I started to double back when I was going to meet people” (McCrum, “My Story”)

Indeed, internet watchdog Citizen’s Lab found a hacker hire-group ‘Dark Basins’ targeted individuals investigating Wirecard’s accounting irregularities. (Murphy) Citizen’s Lab uses Wirecard’s critics as a key example of Dark Basins’ work, stating that “some individuals were targeted almost daily for months, and continued to receive messages for years.” Wirecard has denied using any of these aggressive intimidation tactics.

Intimidation is both directly ethical misconduct and an enabler of such behavior by encouraging people to act against their moral decisions. Intimidation methods like those reported by FT journalists and JCap also go directly against the requisite of transparency as a foundation of a fair financial market. In order to avoid and discourage such unethical practice, there should be greater external protection for whistle-blowers and reporters, like the FT and JCap, by legal or regulatory institutions. This was not the case with Wirecard’s intimidation of the FT and JCap.

The Final Fall of Wirecard

Wirecard seemed to start out strong in its second decade, securing a €900 billion deal with Japanese multinational company SoftBank Group Corp, ranked the 36th largest company in the world by Forbes. EY approved the 2018 accounts. Meanwhile, the FT continues to publish details and instances of irregularities across Wirecard’s different operations, particularly those in Singapore, the Philippines and Dubai which Wirecard continually rejects. The legal war between the FT and Wirecard continued throughout 2019.

After postponing the publication of the 2019 audited annual report, Wirecard revealed that it had €1.9 billion euros missing on June 18th, 2020. On June 22nd the company confessed the “missing 1.9 billion euros of cash probably didn’t exist” (Chanjaroen). This confirmed the longstanding allegations from different sources against Wirecard for accounting irregularities and fraud. When the missing money was first ‘discovered’, Wirecard attempted to throw the blame on Philippine lenders, who in turn denied any business with Wirecard (Batino). Indeed, the Central Bank of the Philippines later confirmed the money never entered the country.

In the week following the lack of publication of the audited report on the re-scheduled date, Wirecard’s shares plunged by 86% (Henning and Arons). COO Jan Marsalek was suspended and CEO Markus Braun was arrested on June 23rd 2020 (Matussek and Syed). The board appoints James Freis as the new CEO on June 19th, his second day of work at the company. Wirecard files for insolvency on June 25th and faces the termination of €800 million worth of loans from lenders on June 30th, with a further €500 million terminating on July 1st 2020 (Syed, Casiraghi, Graber). The insolvency does not cover Wirecard Bank in Munich. Munich prosecutor Wolfang Schirp is leading a German lawsuit against EY for negligence in signing off a 2018 report which contained clear irregularities. BaFin’s president, Felix Hufeld called the Wirecard scandal a “complete disaster”, yet focused blame on Wirecard’s management and the “scores of auditors” who did not adequately notify of irregularities. (Comfort) German Finance Minster, Olaf Scholz, has defended BaFin from increasing scrutiny, and called for changes to regulatory requirements.

The ultimate collapse of Wirecard by the end of June 2020 has unearthed the key players in the ethical dilemmas posed throughout the two decades of Wirecard’s operations.

Ethics Analysis

1 Moral Agents and Key Players

To begin an analysis of the ethics failures that led to the collapse of Wirecard, we first identify all key moral agents, those directly involved, collaterally involved and those involved through consequence. A moral agent can be defined as an individual or corporation that holds moral responsibility because she or it is able to act freely according to reason to resolve moral dilemmas and determine right from wrong. We can both hold entire organizations accountable for their ethical decisions and the executive individuals managing them as responsible within the corporation. It is dubious as to how much blame can be placed on non-managerial roles within corporations. Many argue the key requirement of freedom of choice is limited when an entity works as a tool for another conscious agent.

Below are the main moral agents in the Wirecard scandal.

1.1 Wirecard Management

The signatories of the ‘Responsibility Statement’ for 2018, which assures “a true and fair view of the assets, liabilities, financial position and results of operations of the Group” are Marcus Braun, Alexander von Knoop, Jan Marsalek and Susanne Steidl. This implies they have fiduciary and therefore, ethical responsibility over Wirecard’s operations.

So far ex-CEO Marcus Braun and Oliver Bellenhaus, the Managing Director of the Dubai-based Wirecard subsidiary Cardsystems Middle East FZ-LLC, have been arrested. Germany has issued an arrest warrant for Ex-COO Jan Marsalek, whose location is unknown after immigration records suggesting he was in the Philippines were found to be fake (Lopez). Thus, immediate legal action is largely confined to the prosecution of agents within Wirecard’s Management and its third-party subsidiaries. The arrest of Bellenhaus manifests the significance of third-party proxy companies in countries where Wirecard did not hold a banking licence as central to Wirecard’s fraud.

1.2 EY

EY held a moral duty to oversee and ensure Wirecard was meeting its duty of fair play and transparency. Particularly significant is the presence of a conflict of interest in EY’s audit function. The failure of EY in its negligence in spotting Wirecard’s malpractice sheds light on the conflict of interests present in most audit firms’ work with their clients, an area which clearly requires more regulation in order to ensure ethical standards are met. EY has shown similar negligence with companies NMC Heath and Luckin Coffee in 2020, demonstrating conflicts of interest are endemic within this firm and across this field.

Although ethical issues may be inherent in the field of audit services as it stands, there are nonetheless individual agents involved within EY. Martin Dahmen, Andreas Budde, Andreas Loetscher and Ralf Broschulat were the EY auditors responsible for approving Wirecard’s accounts since 2013. They negligently signed off accounts without fulfilling their audit duties raising questions as to why, as individuals, they chose to look the other way, fail to meet audit standards, and ignore Wirecard’s increasingly evident fraud.

1.3 BaFin

As Germany’s financial regulator BaFin held a moral obligation to ensure Wirecard’s transparency. Of specific significance is its decision to ban short-selling in 2019, and yet not institute a parallel investigation into Wirecard. Similarly, in 2016 BaFin investigated short-sellers without detailed investigation into Wirecard’s compliance problems. Neglect of various reports from The Financial Times starting in 2015 shows a lack of good judgement as regulators.

As president of BaFin, Felix Hufeld is also individually accountable. Likewise, German Finance Minister Olaf Scholz holds moral responsibility to ensure regulatory authorities like BaFin fulfil their obligations. It is reported that ex-CEO Markus Braun and deputy finance minister, Joerg Kukies, held “classified” discussions on November 5th, 2019, increasing suspicions on the extent the finance ministry was directly involved in and aware of Wirecard’s accounting fraud and the fiduciary and regulatory negligence surrounding it.

1.4 The Financial Times

Finally, although an inactive agent in taking decisions concerning Wirecard, The Financial Times is both implicated by consequence and in its own fulfilment of journalism’s purpose and duty in reporting potential wrongdoing. It is key in a discussion of Wirecard’s duty of transparency and honesty. Dan McCrum and other reporters in his team were sued and investigated in 2019 for potential collusion with short-sellers. This raises question over principles of justice as the FT was seemingly placed under more legal scrutiny than Wirecard after the 2019 reports.

2 Wirecard: A Web of Lies

Wirecard built much of itself upon a framework of lies in order to maximise profit and growth. Fraud is defined as deceit with the intention to gain advantage illegally or unethically. Wirecard’s lies therefore developed into wide-scale fraud.

An understanding of the immorality of deceit and lying can be broken down through a deontological approach to ethics, such as Kant’s. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) revolutionized ethics through his deontological-based approach that presents maxims of right and wrong and moral duties humans ought to follow based on pure reason. Kant introduced the idea of the “good will” as the only thing “which can be regarded as good without qualification.” (Kant, 393) He argued one must act out of duty and on the basis of a moral principle. Kant’s categorical imperative, representing a moral ‘ought’ independent of results, removes a result and consequence based, teleological, understanding of morality by creating independent maxims of moral duty and a universal law. Unlike a utilitarian approach which considers the end-result to find “the greatest good for the greater number”, Kant’s deontology sees a duty to follow a universal moral law irrespective of end consequence. For Kant, deceit is one of his universal ‘wrongs’ proven through his 3 formulations.

“Act as if the maxims of your action were to become through your will a universal law of nature.” (Kant, First Formulation)

Following the first formulation, if lying became universal law, the reliability and meaning of language would become void, therefore it could not become a “universal law of nature”. Likewise, individuals would be unable to make free rational choices as the information used to make these decisions would be false and manipulated through deceit. With Wirecard’s fraud, if everyone deceived investors through inaccurate accounting and inflation of profits no one would invest. Moreover, fraud denies a client in a transaction her freedom to make rational decisions, as these decisions are based on deceit and lies. Thus, according to Kant’s deontological ethics, the act of lying, like fraud, cannot be universalized and is therefore, immoral.

In contrast, the Utilitarian view could argue fraud was not unethical if it meant a larger proportion of people benefitted from it. For example, the case could be made that fraud leads to a ‘greatest good for the greatest number’. With Wirecard, fraud allowed for the growth of Wirecard therefore gave more jobs and overall wealth increasing individual livelihoods. However, Edwin R. Micewski and Carmelita Troy argue against the use of utilitarian ethics in business. They conclude that because harm endured in business is “usually limited to loss of material property”, not a loss of human life or health, the consequentialist, teleological analysis falls apart (19). They assert that “ethics devoid of deontological ingredients, that is, ethics that focuses primarily on the consequences and not on the rightness or wrongness of the act itself, is, in the end, no true ethics at all”, especially in the field of business ethics (Micewski and Troy, 19).

The Financial Times’ allegations in 2019 accused Wirecard of practicing ‘book-padding’, ‘round-tipping’, and ‘backdating’ amongst other accounting irregularities and fraud, particularly in its Asian operations. All of these malpractices are unethical because of the core immorality of deceit. In accounting, ‘book-padding’ refers to the presentation of inflated or false entries into a company’s accounts. Some companies attempt to justify small amounts of ‘padding’ as foresight, for example, presenting it as a way to take into account general inflation. Nevertheless, it is inherently deceitful and fraudulent in not reflecting accurate data to investors and shareholders. The FT argued Wirecard inflated its accounts in order to “create figures that would convince regulators at the HK Monetary Authority to issue a licence so Wirecard could dole out prepaid bank cards in the Chinese territory.” This further maximises the wrongfulness of the action in using deceit as a means to an end. Following Kant’s second formulation:

“act in such a way that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never merely as a means to an end but always at the same time as an end” (Kant, Second Formulation)

Wirecard deceived regulators in order to use them as a means to a fraudulent end. Similarly, when auditors found the €1.9 billion hole in Wirecard’s accounts, Wirecard’s management falsely tried to shift responsibility to two of its Filipino lenders: BDO Unibank and the Bank of Philippine Islands (BPI), the country’s largest banks. Wirecard attempted to discredit these banks in order to hide their wrongdoing. Benjamin Diokno, the current Governor of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas and the Chairman of the Anti-Money Laundering Council proved the missing money never entered the country, suggesting “the international financial scandal used the names of two of the country’s biggest banks – BDO and BPI – in an attempt to cover the perpetrators’ track” (Dela Cruz). Wirecard forged certification of deals with these banks, as revealed by the BPI, again using the entities as means to a self-profiting end and breaking its duty to fair play and truth.

2.1 Escrow Accounts

Wirecard’s use of escrow accounts as a veil to their fraud suggests a need for greater oversight on these financial instruments, especially from auditors. On principle, escrows were developed in order to prevent malpractice, ensuring parties paid one another and provided services promised through a moderation of funds by a third-party. These escrow accounts allowed Wirecard to do business in countries where it didn’t have a licence, such as Singapore, Malaysia and Dubai among others, through small, local third-party payment companies. The revenue obtained from these were supposedly placed in escrow accounts. Indeed, Wirecard claimed the €1.9 billion missing cash was held in escrow accounts. However, EY continually failed to properly verify the existence of this cash. As escrow accounts hold cash outside the company’s primary cash-flow it is easier for deception to take place using them. Furthermore, it immorally implicates third-party agents within the fraud. The FT Alphaville series on Wirecard (2015) explains irregularities in excessive profit growth from these third-party companies in non-licensed countries. In hindsight, this showed early evidence of the use of escrow accounts to cover up fraud and revenue inflation. Indeed, the 2015 JCap report claimed many of the third-party payment companies were largely non-existent or incompatible with the large operations they supposedly undertook. Thus, the Wirecard fraud centred around these overlooked escrow accounts, which were inadequately regulated and verified by auditors, despite the large sums of money allegedly held in them.

3 Transparency and Commutative Justice

The duty of transparency is a core moral principle in financial ethics. It is established upon two key ideas: the notion of justice, in particular ‘commutative justice’, and the Rawlsian ‘duty of fair play’. Rawls’ ‘duty of fair play’ is a development from Hobbes ground-breaking social contract theory and Kantian deontology. Rawls argues “society’s main political, constitutional, social, and economic institutions and how they fit together to form a unified scheme of social cooperation over time” (Rawls, 15). Mutual transparency in the financial markets is a “unified scheme of social cooperation”, if all parties abide by their duty of transparency. Central to Rawls’ “justice as fairness” argument is the idea of obligation to a law. In finance, this ‘law’ is represented by regulators whose role is to uphold principles mutually agreed to be considered fair. Transparency is one of the mutually agreed principles of fair play in the ‘social contract’ of finance.

The Seven Pillars Institute describes commutative justice as “fairness in the exchange of goods or services” (SPI, “Financial Crisis 2008”). Central to this mode of justice is the idea “each party must enter into the transaction freely and not be coerced” (Ibid.). Indeed, the financial market is built upon the axiom of commutative justice. John R. Boatright views a financial transaction “as a type of promise”, relying on the “basic moral duty to keep all promises made” (18). Extending the pre-requisite that a moral agent has freedom of choice, an individual involved in a transaction must have “information symmetry” (Ibid.). Peter Koslowski outlines 4 key requisites for commutative justice in finance: (1) a reflection of market price; (2) appropriate exchange; (3) mutual advantage and benefit; (4) balance of interests. Koslowski’s requisites refer to ideas of contractual relationship between individuals in the pursuit of morality. Through its fraud and profit inflation, Wirecard failed to present an accurate reflection of its market price. Shareholders and investors entered transactions under the impression that Wirecard had a larger market capitalization and future expected growth. This information asymmetry and false reflection of the company’s market value because of Wirecard’s fraud constitutes an inappropriate exchange with investors and breaks the principles of commutative justice.

Yet, scandals revolving around accounting irregularities and fraud are not uncommon within the financial industry. As a result, multiple external mechanisms with a duty to foster transparency and commutative justice have been developed. The failure of these fiduciary and regulatory mechanisms in the Wirecard scandal shows inherent flaws in their structure.

4 EY’s Conflict of Interest

In response to the Wirecard scandal, EY stated: “There are clear indications that this was an elaborate and sophisticated fraud involving multiple parties around the world in different institutions with a deliberate aim of deception” (Deutsche Welle). However, EY fails to see its complicit role within this “elaborate and sophisticated fraud”, centering around a conflict of interest. If there are such ‘clear indications’ of such a large-scale fraud, why did EY fail to see it sooner?

Conflicts of Interest “jeopardize an individual’s ability to act ethically by interfering with his or her capacity to exercise good judgment. This interference may lead to wilful neglect of the individual’s professional or public obligation” (SPI, “Conflict of Interest”).

The established obligation of EY’s audit branch is to ensure regulatory requirements are upheld. The firm’s stated aim is to “help [organizations] fulfill regulatory requirements, keep investors informed and meet the needs of all of their stakeholders.” This enshrines its obligation to supervise an organization’s duty of transparency towards their investors within the financial market as central to its aims and moral purpose. However, the client-based relationship between the audit firm and its client, in this case EY and Wirecard respectively, creates a conflict of interest.

Boatright argues conflicts of interests are widespread and unavoidable in the financial sector, stating they “are built into the structure of our financial institutions and could be avoided only with great difficulty.” He distinguishes between personal and impersonal conflicts of interests, with the latter being more common. Indeed, in this case, the conflict of interest within EY is built into the service it provides, institutional and therefore, impersonal. These conflicts of interests take place because the firm is supposed to serve interests other than their own. It is in EY’s interest to sign off Wirecard’s accounts so that it continues to be hired and have a recurring, stable client. However, it is EY’s duty to serve the universal, non-personal, duty of transparency over both their clients’ and their own interests.

Following the Wirecard scandal, the UK’s Financial Reporting Council (FRC) responsible for regulating auditors, accountants and actuaries announced that the ‘Big Four’ accounting firms – EY, Deloitte, KPMG, PwC – had to separate their audit units from other operations by June 2024. This is a step in the right direction towards minimizing the structural conflict of interests in the sector. Other countries should follow in the FRC’s footsteps and pass similar regulations.

5 Looking the other way: BaFin, Regulatory Capture and Negligence

In Germany, BaFin is the Financial Supervisory authority obliged to ensure all parties fulfil their duty of transparency within the German financial market. This includes both the primary duty held by Wirecard, and the oversight duty held by EY. As a regulatory agency, BaFin failed to regulate both Wirecard and EY’s operations, neglecting various signs of unethical practices.

BaFin’s negligence could be a result of regulatory capture. Regulatory capture is an economic theory which argues regulators can become more influenced by the interests of those who they regulate than the public interest. The regulators therefore serve the commercial interests of those who dominate the industry, the firms they are supposed to regulate. This theory is often attributed to Nobel laurate economist George Stigler and his work The Theory of Economic Regulation (1971).

The opposing economic theory to regulatory capture follows the public interest paradigm, which holds that regulatory agencies benevolently serve the public interest to improve social welfare. Regulatory Capture theory usefully helps understand how collusion can take place, rather than ignoring its possibility. It aims to explain why regulatory agencies often fail to enforce the law against the companies they are regulating. When a regulatory agency is ‘captured’ it poses a great threat as it holds the authority of government yet uses it against the public interest it is supposed to serve. Regulatory capture can occur through various methods, for example: the development of close relationships between regulators and companies; information asymmetry coming from the firm; and, the possibility of corruption, among others.

The three-step model of regulatory capture understands its functioning through a hierarchy: first, the political principal (German government in Wirecard’s case); second, the regulator (BaFin); and third, the agent (Wirecard). This model was proposed by Tirole in 1986, following from Stigler’s work. This helps visualize the key entities holding moral agency in a given instance of potential capture, such as in the Wirecard scandal.

In the case of BaFin, the government’s interest may have become ‘captured’ by Wirecard’s fraudulent interests because of its seeming success. The information asymmetry and fraudulent accounting made Wirecard appear to be Germany’s, and indeed, Europe’s biggest and most successful technology company. In all likelihood, the company’s apparent success accounts for why BaFin, backed by the finance ministry repeatedly sided with Wirecard and vouched for its honesty, despite growing evidence against it over the 2010s. Supporting Wirecard was in the government’s interest because maintaining Wirecard’s success fostered investor faith and optimism in German tech, favouring Germany over long-time leaders in the field such as the USA. There may have been a favouring of reputation, fuelled by Wirecard’s deceit, over social welfare and the public interest by both the government and thus, BaFin.

The head of BaFin, Felix Hufeld, attempted to circumvent direct blame by stating that “Wirecard’s top management as well as “scores of auditors” failed to act or realize what’s going on”, without directly recognizing the need to change within his own organization. This arrogant approach to the scandal undermines the future potential of genuine self-reflection and developing a stronger mechanism that ensures transparency and fair play in finance.

6 Conclusion

As the multiple legal procedures take place against individuals within the Wirecard management, it is important to emphasize the responsibility held by external regulators BaFin and EY. Although a prosecution has been opened against EY by Wolfgang Schirp, there has been no direct investigation into BaFin’s negligence and potential ‘capture’ throughout Wirecard’s long history of accounting irregularity and fraud. In order to use the scandal of Wirecard as a lesson to avoid regulatory capture, BaFin should be held accountable as much as EY or Wirecard’s management, albeit with differing methods of redistributing justice. Where individuals like Markus Braun and Jan Marsalek will most likely need to serve retributive justice because of their direct immoral acts of fraud and deceit, Wirecard’s scandal sheds light on the need for reform of regulatory authorities within the financial market in order to ensure commutative justice and duty of fair play is upheld.

Latest Update on Wirecard

Since June, further investigations and prosecutions have taken place in response to Wirecard’s fraud. Between July and August, German state prosecutors arrested multiple former executives of Wirecard. In August, Deutsche Boerse removed Wirecard from the DAX index. Wirecard was forced to terminate its services in Singapore in September, whilst fugitive Jan Marsalek is still on Interpol’s ‘red list’. In November, Spanish bank Santander acquired Wirecard’s European arm for €100 million, following Syncapay’s acquisition of the North American branch in October. The UK business was acquired by Railsbank in August, and Brazil’s PagSeguro Digital bought Wirecard’s Brazilian business. Clearly, Wirecard’s insolvent businesses is slowly being acquired across all operational regions by multinational banks and smaller start-ups alike.

With regards to the greater impact Wirecard’s collapse had on the regulatory and auditing agencies, such as Germany’s BaFin and the ‘Big Four’, little concrete change has taken place as of yet. Nevertheless, the German government has drafted bills looking to: (1) impose greater independence and accountability on auditing firms and individual auditors, allowing for more robust means of punitive justice; (2) grant BaFin greater regulatory powers and freedom to investigate suspected fraud; (3) force rotation of auditors each decade; and (5) limit client overlap between firm’s consultancy and auditing practices. If these bills pass despite opposition from auditors and organizations like the German chamber of Public Accountants (WPK), they would be steps in the right direction towards greater accountability and acceptance of moral responsibility. Meaningful change would turn Germany and Europe’s largest case of accounting fraud in this decade into a positive restructuring of the audit and regulatory sector, which other countries, beyond Germany and the EU, should implement for greater accounting transparency.

Works Cited

“Financial Crisis 2008, Perpetrators, and Justice.” Sevenpillarsinstitute.org. Seven Pillars Institute for Global Finance and Ethics, 23 May 2013. Web. 15 June 2020. <https://sevenpillarsinstitute.org/financial-crises-perpetrators-and-justice/>.

“Conflict of Interest” Sevenpillarsinstitute.org. Seven Pillars Institute for Global Finance and Ethics, 26 Aug 2017. Web. 15 June 2020.<https://sevenpillarsinstitute.org/glossary/conflict-of-interest/>

“Wire Card AG Plans to Acquire XCOM Bank AG.” TeleTrader.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 June 2020. <https://www.teletrader.com/wire-card-ag-plans-to-acquire-xcom-bank-ag/news/details/2190273?internal=1.>.

Batino, Clarissa. “No Missing Wirecard Funds in Philippines, Central Bank Says.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 21 June 2020. Web. 21 June 2020. < https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-06-21/no-missing-wirecard-funds-entered-philippines-central-bank-says>.

BÓ, ERNESTO DAL. “REGULATORY CAPTURE: A REVIEW.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy, vol. 22, no. 2, 2006, pp. 203–225. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23606888. Accessed 20 July 2020.

Boatright, John Raymond. Ethics in Finance. Somerset, NJ: Wiley Blackwell, 2014. Print.

Boerse.ARD.de. “Auf Und Ab: Der Fall Wirecard: Börsengeschichte.” Boerse.ARD.de. N.p., 31 Jan. 2019. Web. 23 June 2020. <https://boerse.ard.de/boersenwissen/boersengeschichte-n/auf-und-ab-der-fall-wirecard100.html>.

Chanjaroen, Chanyaporn. “Wirecard (WDI DE) Says Missing Cash May Not Exist, Pulls Results.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 22 June 2020. Web. 21 June 2020. <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-06-22/wirecard-says-missing-cash-likely-doesn-t-exist-pulls-results>.

Comfort, Nicholas. “Wirecard Scandal a ‘Complete Disaster,’ Says Germany’s Bafin.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 22 June 2020. Web. 22 June 2020.

Cruz, Enrico Dela. “Wirecard’s Missing $2.1 Billion Didn’t Enter Philippine Financial System, Central Bank Says.” Reuters. Thomson Reuters, 22 June 2020. Web. 22 June 2020. <https://fr.reuters.com/article/businessNews/idUKKBN23S03R>.

Deutsche Welle News. “Wirecard Committed ‘elaborate and Sophisticated Fraud’ Say Auditors: DW: 25.06.2020.” DW.COM. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 July 2020. <https://www.dw.com/en/wirecard-committed-elaborate-and-sophisticated-fraud-say-auditors/a-53942273>.

Gavin, Mike. “Wirecard Proposes 2009 Dividend, Confirms 2010 Target.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 15 Apr. 2010. Web. 30 June 2020. <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2010-04-15/wirecard-proposes-2009-dividend-after-full-year-revenue-ebitda-increase>.

Henning, Eyk, and Steven Arons. “Wirecard Said to Have Explored Deutsche Bank Tie-Up in 2019.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 22 June 2020. Web. 22 June 2020. <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-06-22/wirecard-said-to-have-explored-deutsche-bank-tie-up-in-2019>.

John Rawls, A Theory of Justice: Revised Edition. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press,1999. Print.

Kant, Immanuel. Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2019. Print.

Kinder, Tabby, Olaf Storbeck, and Stefania Palma. “EY Failed to Check Wirecard Bank Statements for 3 Years.” Financial Times, 26 June 2020. Web. 26 June 2020. <https://www.ft.com/content/a9deb987-df70-4a72-bd41-47ed8942e83b>.

Koslowski, P. Principles of Ethical Economy. 2001.

Lopez, Ditas B. “Faked Philippine Records Left False Trail for Wirecard Exec.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 04 July 2020. Web. 4 July 2020. <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-07-04/faked-philippine-records-left-false-trail-for-wirecard-executive>.

Maley, Karen. “‘There Was Speculation about Kidnap Threats’: J Cap.” Australian Financial Review. N.p., 22 June 2020. Web. 2 July 2020. <https://www.afr.com/companies/financial-services/aussie-researcher-questioned-embattled-german-fintech-wirecard-20200622-p554v7>.

Matussek, Karin, and Sarah Syed. “Former Wirecard CEO Arrested Amid Widening Criminal Probes.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 23 June 2020. Web. 23 June 2020. <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-06-23/wirecard-s-former-ceo-braun-arrested-in-accounting-scandal>.

McCrum, Dan. “JCap on Wirecard: A Search for the Asian Business.” FT Alphaville. N.p., 20 Nov. 2015. Web. 1 July 2020. <https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2015/11/20/2145256/jcap-on-wirecard-a-search-for-the-asian-business/>.

McCrum, Dan. “The House of Wirecard.” FT Alphaville. N.p., 27 Apr. 2015. Web. 2 July 2020. <https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2015/04/27/2127427/the-house-of-wirecard/>.

McCrum, Dan. “The Strange Case of Ashazi: Wirecard in Bahrain, via Singapore.” FT Alphaville: House of Wirecard. N.p., 5 May 2015. Web. 27 June 2020. https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2015/05/05/2127886/the-strange-case-of-ashazi-wirecard-in-bahrain-via-singapore/

McCrum, Dan. “Wirecard and the Missing €1.9bn: My Story.” Financial Times. Financial Times, 26 June 2020. Web. 20 July 2020. <https://www.ft.com/video/37cb70e6-72df-471e-943d-2d32c2785650>

McCrum, Dan. “Wirecard: The Timeline: Free to Read.” Financial Times. N.p., 25 June 2020. Web. 25 June 2020. <https://www.ft.com/content/284fb1ad-ddc0-45df-a075-0709b36868db>.

Micewski, Edwin R, and Carmelita Troy. “ Business Ethica: Deontologically Revisited .” Journal of Business Ethics 72, no. 1 (April 2007): 17–25.

Morgan, Jonathan. “Wirecard Gains as Goldman Forecasts Strong Revenue Growth.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 04 Sept. 2013. Web. 25 June 2020. <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-09-04/wirecard-gains-as-goldman-forecasts-strong-revenue-growth>.

Murphy, Paul. “Hackers for Hire ‘targeted Hundreds of Institutions’.” Financial Times, 09 June 2020. Web. 3 July 2020. <https://www.ft.com/content/315aceba-935a-4e70-83c4-1d1fd7cf939b>.

Nicola, Stefan, and Claudia Rach. “Wirecard Jumps Most in Week as CEO Unfazed by Zatarra Report.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 02 Mar. 2016. Web. 5 July 2020. <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-03-02/wirecard-jumps-most-in-week-as-ceo-unfazed-by-zatarra-report>.

Palma, Stefania, and Dan McCrum. “Wirecard: Inside an Accounting Scandal.” Financial Times. N.p., 07 Feb. 2019. Web. 15 June 2020. <https://www.ft.com/content/d51a012e-1d6f-11e9-b126-46fc3ad87c65>.

Smith, Geoffrey. “Meet the German Fintech That’s Now Worth More Than Deutsche Bank.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 14 Aug. 2018. Web. 23 June 2020. < https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-08-14/meet-the-german-fintech-that-s-now-worth-more-than-deutsche-bank>

Syed, Sarah, Luca Casiraghi, and Fabian Graber. “Wirecard (WDI DE) Files for Insolvency as Billions Go Missing.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 25 June 2020. Web. 25 June 2020 <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-06-25/wirecard-files-for-insolvency-after-2-1-billion-went-missing>.

Thompson, Mel. Ethical Theory: Fourth Edition. London: Hodder Murray, 2008. Print.

Zatarra. “Wirecard AG (WDI GR): Wide Scale Corruption and Corporate Fraud.” Zatarra Research & Investigations. N.p., 24 Feb. 2016. Web. 1 July 2020. <https://www.heibel-unplugged.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Zatarra-research-Wirecard-PDF.pdf>.

Photo courtesy of dw.com