Covid-19 Pandemic Worsens Inequality

By Carmen Pegas

Covid-19 Pandemic and Inequality

COVID-19 highlighted inequalities in our societies. Half the global population lost income during the pandemic (1). By 2022, global unemployment will exceed 200 million workers (2) and 150 million people will be pushed into extreme poverty (3). Low-income and low-skilled workers shouldered the brunt of job and income losses (4). Meanwhile, the 2,365 world’s billionaires, enjoyed a 54% boost in their wealth during the pandemic, equivalent to an increase of 5 trillion dollars (5). To put these numbers into perspective, the wealth increase of the 10 richest men over the pandemic ($540 billion) could pay for everyone’s vaccines globally (6).

Economic inequality is defined as the disparities in wealth and income in a society or group (7). It encompasses incomeinequality, the unequal distribution of income received for providing labour or investing in capital, and wealth inequality, the unequal distribution of assets of value (8). Economic inequality has been on the rise for decades (9) and COVID-19 worsened this problem. These disparities have not gone unnoticed by communities and prominent institutions. A growing demand confronts governments for policies that tackle inequality, including wealth and global minimum corporate taxes and increases in welfare spending to support those facing financial hardship (10). Crises can incite reform, so leaders should seize this opportunity to address the rising inequalities the pandemic exacerbated.

Economic Inequality

- Inequality Pre-Pandemic

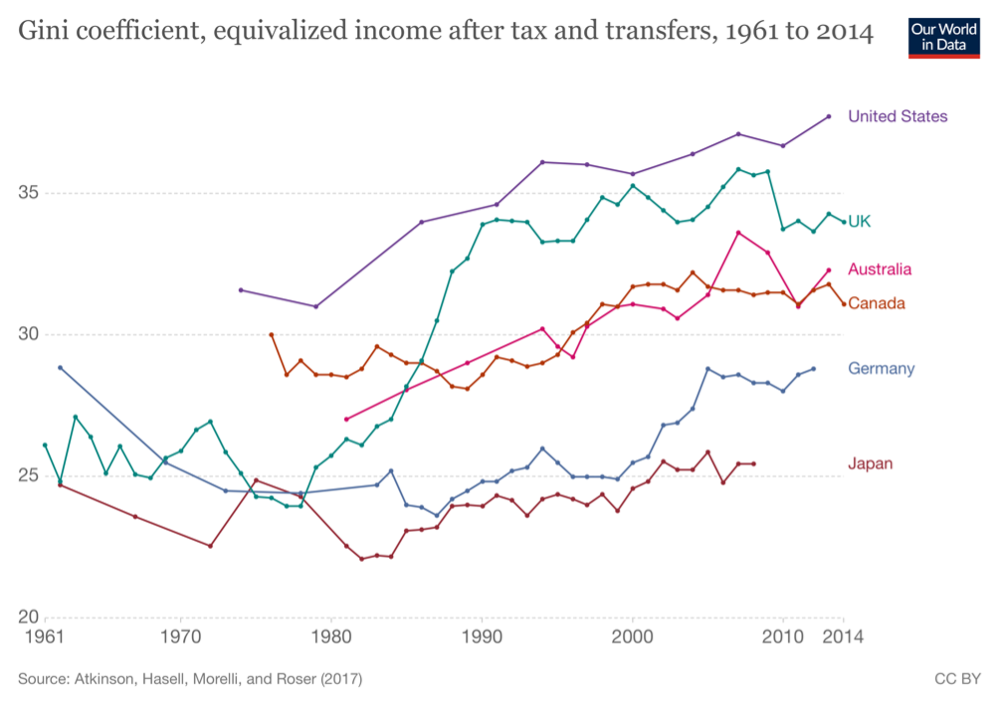

Since the 1970s, income inequality has been on the rise in most advanced economies (11), especially in English-speaking countries such as the US and the UK (12).

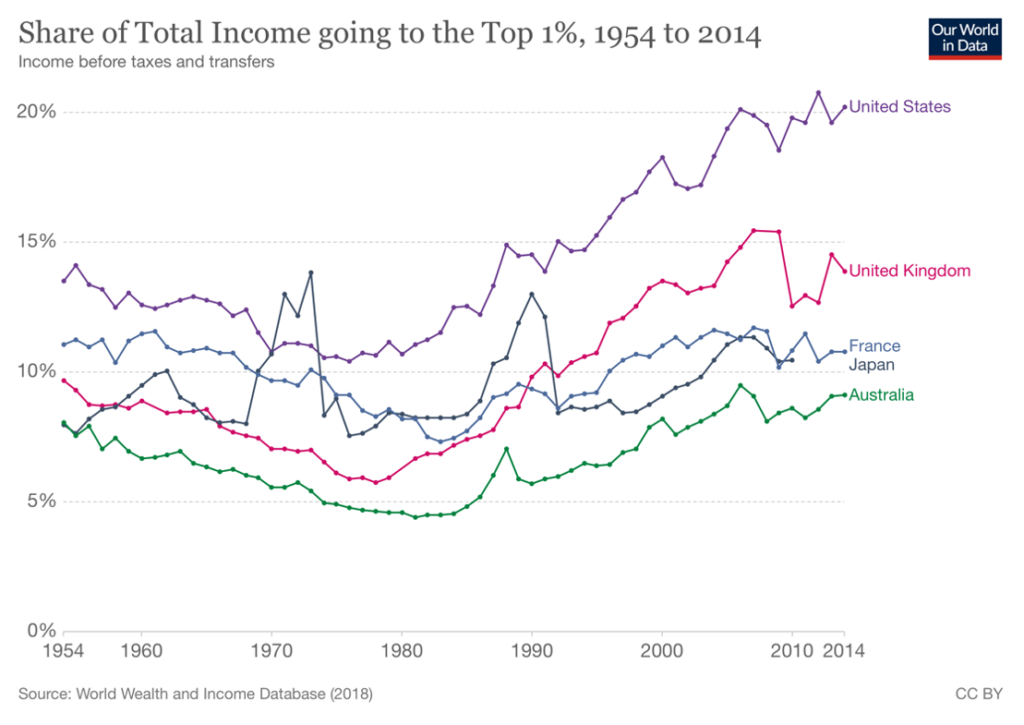

The Gini coefficient, the most pervasive measure of income inequality, quantifies how unequal a society is, where 0 represents total equality and 100 represents a single person owning all the society’s income. Its increase is shown in Chart 1. Although the graphs show an upward trend in inequality, they omit some very relevant trends, like the enormous increase in the income held by the top 1%, as noted by the deputy director at the IFS, Robert Joyce (11). Decile dispersion ratios unmask the true extent of inequality by comparing the average income of the richest x% to the average income of the poorest x% (13). These ratios show that the top 1% earned more than double the income of the bottom half of the population in recent years (14). We should be wary of associating economic growth with better standards of living for the population. In the US in the 2000s, for example, the top 1% took 58% of the gains in real income, so the improvement in the population’s financial wellbeing was benefiting a much smaller group than the statistics suggest (15).

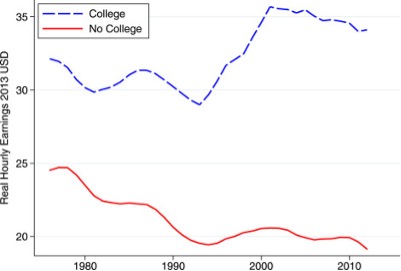

The causes for this increase in inequality are varied and hotly debated. Firstly, technology has had a big impact in the labor market. Technological change devalues jobs involving routine manual and cognitive tasks because they are easily and cheaply replaced by machines. For example, in the U.S. automotive industry, employing a spot-welding machine costs $8 an hour and a worker $25 (16). Technological advancement also values high skilled jobs responsible for operating and creating new technology. This explains why the income gap between high- and low-skilled has been growing (see Chart 3 for evidence in the US).

Secondly, the way income is distributed changed. Income can be earned by owning physical capital, land, or a business – capital income – or by holding a paid job – labor income (17). The capital owners’ share of income is increasing, and the share of income received by workers is falling, in what appears to be a global phenomenon. The labor share of income across OECD countries fell from around 66% in the early 90s to 61.7% percent in the late 2000s (12). OECD estimates technology and automation account for 80% of the shift. So, income that used to go to workers now goes to owners of capital who financed machines and informational systems that replaced those workers (12). In G20 countries, a 1% reduction in the labor income share leads to a 0.1 to 0.2% increase in inequality in market income (18). This trend can aggravate wealth concentration because newly created wealth is going to be concentrated in already wealthy individuals that own capital.

Lastly, institutional factors may have played a role in the rise of inequality. Since the late 1970s, developed economies have increasingly become less regulated. Before, governments played a more active role in the labor force by negotiating wage rises at the national level and more strongly regulating when firms could let workers go (12). This liberalization of labor markets led some low-skilled low-income workers, particularly temporary workers, to have weaker employment protection than before. Simultaneously, as the labor market became more competitive, high-skilled workers saw their wages increase due to a higher demand for their labor (19). Taxation’s redistributive role might have also weakened. Although income taxes have become more progressive over the last few decades, the average top statuary tax rate (12) and corporate tax rate have both substantially decreased since the 1980s globally (20).

- Inequality During and After the Pandemic

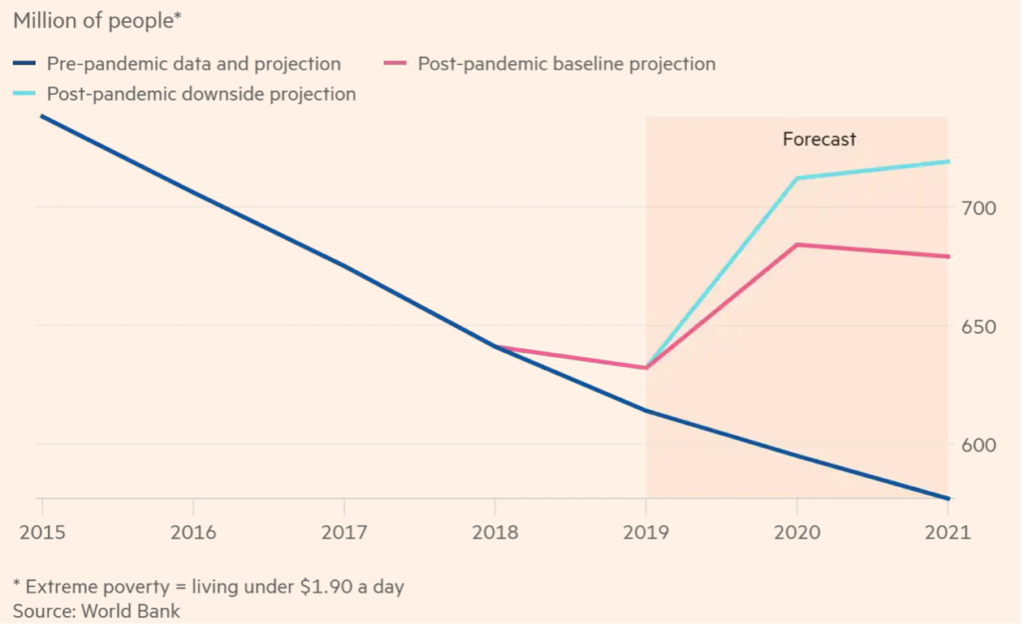

The COVID-19 pandemic hit a world already struggling with rising inequality and exacerbated the problem. A CEPR study on past pandemics concluded that they increase income inequality by damaging employment prospects of less skilled workers while barely impacting educated workers (21). The impact of COVID-19 on the labor market, unfortunately, followed this pattern. As a result, extreme poverty, which has followed a downwards trajectory in the last few decades, is forecast to increase (See Chart 4). The pandemic increased economic inequality through four main channels.

Firstly, informal employees, over 2 billion workers worldwide, and non-traditional employees have been disproportionally impacted (22). These include workers in activities undeclared to tax authorities and those in “alternative working arrangements” such as independent contractors, temporary help agency workers and freelancers. These jobs are usually low-paid and lack social protection benefits (23). During the pandemic, employers could quickly let go of these workers without the official procedures required for formal employers, shifting the cost of the drop in aggregate demand to workers. The International Labor Organization projects poverty will increase by 52 points in high-income countries and by 56 in low-income countries as a direct result of the pandemic’s impact on informal workers, who make up 62% of the workforce worldwide and 90% of the work force in low-income countries (22). These workers, who in low-income countries are mainly women (24), are usually in precarious financial situations and cannot rely on savings or government aid such as unemployment benefits to fulfill their basic needs. As a result, many of the poorest workers worldwide are seeing their income dangerously reduced.

Secondly, low-paid, low-skilled workers are more likely to work in industries that suffered with lockdowns, such as hospitality and retail, and consequently to have suffered job or earning losses (25). Notably, a high proportion of women, migrants, and ethnic minorities are employed in these sectors (25). Due to the inability to conduct many activities face-to-face, businesses automated jobs performed by low-skilled and medium-skilled workers (26). Having to work remotely exacerbated the disparities between workers further, with less than 20% of low-income workers able to work from home, as opposed to 40% of skilled workers (27). As a result, lower-income workers report being more negatively impacted by the pandemic than higher-income workers (See Chart 5) (25).

Thirdly, since the historic drop in the Dow immediately after COVID-19 was labeled a pandemic, financial asset prices have risen, in some cases to record highs (28), partly due to central banks’ efforts to stimulate economic activity, like cutting short-term interest rates and injecting money stimulus into the global economy (29). According to a UBS report, very wealthy individuals profited from betting on the recovery of stock markets after the initial drop in asset prices (30).

Fourthly, the pandemic disproportionally affected small business, which lacked the liquidity and access to loans necessary to survive prolonged periods of inactivity (31). In the US, 34% of small businesses closed due to COVID-19 (32). The business closures will increase larger firms’ market shares, exacerbating the current trend towards less competitive and more oligopolistic markets (33). Large firms also funnel a smaller share of their earnings to workers and instead direct more profits to wealthy owners and investors (34). This distribution profile will decrease the share of national income paid to workers through salaries and wages and reinforce the increase in capital income shares, fueling inequality.

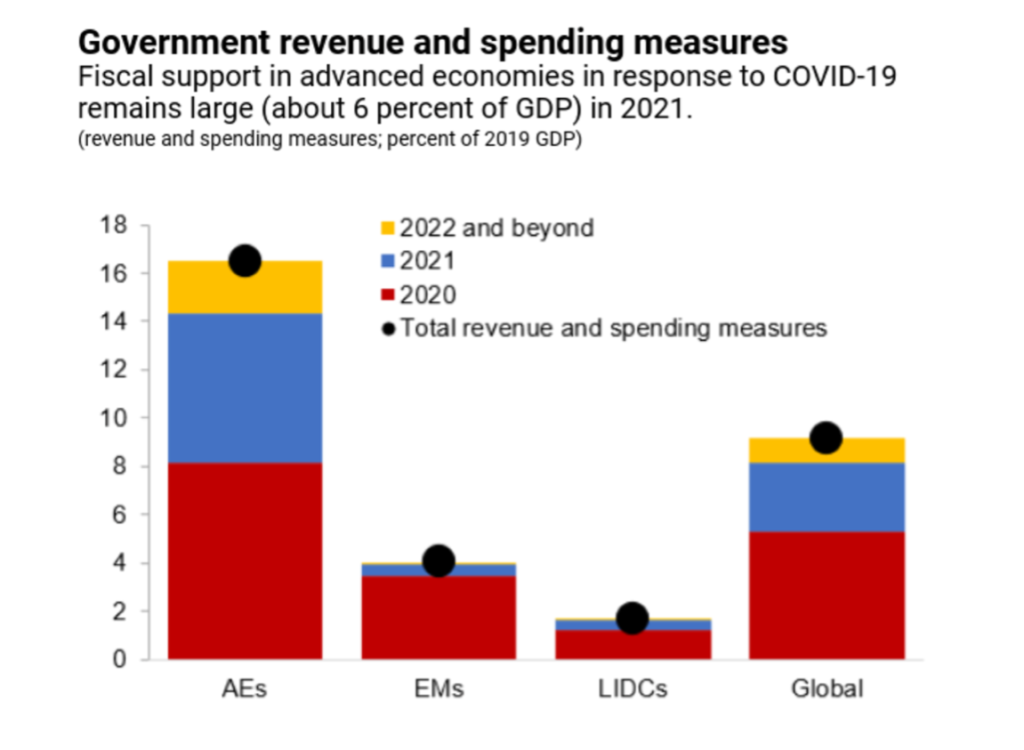

Globally, the divide between developed and developing worlds is likely to sharpen, as some of the major economies are enjoying a fast recovery while others are being left behind. Rich countries dominated access to COVID-19 vaccines, allowing them to ease restrictions and kickstart economic activity much faster than developing countries (35). By April of 2020, 1 in 4 people had been vaccinated in high-income countries as opposed to 1 in 500 in poorer countries (36). Richer countries could also afford costly fiscal measures to protect their economies, preventing a more severe loss of employment and economic contraction (Chart 6). Fiscal support was much more limited in developing countries due to financial constraints and rising public debt (37). According to IMF and World Bank reports, Latin America and the Caribbean experienced their worse economic contraction ever (38), and sub-Saharan Africa experienced its first economic recession in 25 years (39).

Changing Attitudes Towards Inequality

Despite these troubling statistics, the pandemic can be a catalyst for change, an opportunity to “renegotiate the social contract”, as said by Francisco Ferreira, director of the International Inequalities Institute at the LSE (10). Influential organizations have expressed support for policies that appeared unthinkable pre-pandemic. The IMF advised advanced economies to use progressive taxation to tackle income inequality and even consider a wealth tax to raise revenue during the pandemic (40). This position represents a shift from its previous focus on tax cuts. Central banks in the US and Europe are addressing income inequality for the first time ever (10). The Chairman of the World Economic Forum, Klaus Schwab, stated that “we must move on from neoliberalism in the post-COVID era” (41). And these opinions represent just some of the many prominent voices that spoke out about the unsustainable economic status quo (42).

The broader population also expresses rising concern for these issues, mostly as a direct result of the pandemic. In a Center on International Cooperation global survey, 64% of respondents agree COVID-19 convinced them “something must be done to more fairly distribute our country’s wealth and prosperity” (43). Support for social policies that provide immediate financial assistance to the most vulnerable soared during the pandemic in the UK, America, Japan and parts of Latin America and Europe, as voters want governments to do “whatever it takes” to aid those in need and not focus on debt (44). Policymakers have started to respond to constituents’ needs, by providing wage subsidies and relief from payment of utilities, rent and debt (45).

But why this shift in mindset? A recent study on inequality aversion – that is, how much a society is willing to renounce to achieve a more equal distribution of wellbeing – concludes that pandemics might make people more averse to inequality (46), both in terms of health and of income. This conclusion may be related to how legitimate people think the causes of income inequality are. Another study done on the topic supports this hypothesis. It finds that after the COVID-19 pandemic, American participants changed what they viewed as the main causes of poverty in their country, reporting that poverty is more linked to external or situational causes than to internal or dispositional causes (47). During the pandemic, billions saw their livelihoods threatened through no fault of their own, by an exogenous factor out of their control. Many might have picked up on this situation and been encouraged to change their perspective on income inequality.

Ethics Evaluation

Luck egalitarianism posits inequality in well-being or wealth are only legitimate if they are not based on unchosen and random circumstances.

Ethics might be a helpful guide to explain this shift in mindset, particularly by justifying when and why people value equality. Egalitarianism is a trend of thought that favors equality of some sort. It encompasses various egalitarian doctrines that highlight and value different types of equality for different reasons (48). Luck egalitarianism posits inequality in well-being or wealth are only legitimate if they are not based on unchosen and random circumstances (49). To luck egalitarians, it is unjust for some to be worse-off through no fault of their own, through reasons other than the choices they make. Most people can get on board with this view to a certain extent: consider two people, equally qualified, who have a job interview for the same job. Person A, on their way to the interview, gets into an accident caused by another driver and is unable to make the interview that day. Many would agree that person B getting the job as a direct result of this is not as just as them getting the job because they performed better in the interview.

COVID-19 might have triggered a similar luck egalitarian response in people. Having an exogenous and unforeseen factor such as a pandemic deepen the divide between the rich and the poor is more likely to be perceived as unjust because luck (or lack thereof), and not personal choice, is responsible for this increase in inequality.

Building Back from COVID-19

A rise in inequality in the long run is not inevitable. Governments have an opportunity to enact inclusive policies that target economic inequalities, especially now that support for them has increased. Promising measures have been taken. In the UK, welfare benefits were extended to those previously ineligible, including many self-employed and informal workers (50). In many countries, including the United States and Australia, eligible citizens received direct payments to compensate for loss of income due to COVID-19, which can prove to be a precursor of Universal Basic Income (51). However, widespread support for expansive social measures goes way beyond the ones needed to provide relief from the pandemic (43). States should utilize the momentum from this crisis to enforce needed reforms.

- Fiscal Measures

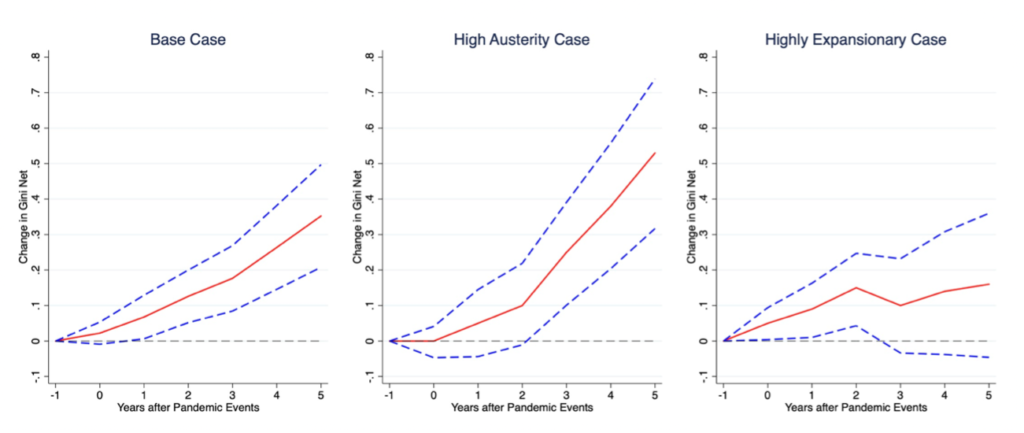

Although social spending has gone up during the pandemic, governments should be wary of implementing fiscal consolidation measures – commonly referred to as austerity – to rein in debt. An IMF paper on OECD countries reports these policies aggravate economic inequality. “Times of austerity” are linked with increases in the Gini coefficient and long-lasting decreases in the labor’s share of income (52). Another study finds similar effects of fiscal austerity in the aftermath of pandemics (53), which explains why many have spoken out against premature withdrawal of fiscal support, even despite increases in public debt (54). That same study also finds that expansionary fiscal policy – fiscal policy that encourages economic growth through government expenditure and tax cuts (55) – actually thwarts increases in inequality.

Historical evidence from the Great Depression and the Great Recession are congruent with this conclusion. Strengthening public services and social protection programs as well as enacting measures to protect the labor share of income led to a reduction in inequality after the initial shock of the crisis (56). The COVID-19 crisis highlighted the importance of social services and safety net programs. The expansion and universal provision of quality education and healthcare are a crucial step towards attenuating economic inequality. Low-income families have more barriers to access healthcare (57) and low-income students (in America, many of whom African American and of Hispanic descent) were disproportionally affected by the shift to online learning because they lacked the technology necessary to access virtual classroom activities (58).

- Taxation

Governments will need to raise revenue to handle the high level of public debt resulting from necessary but costly expenditure during the pandemic and funding of welfare programs. To prevent an even higher rise in inequality, middle- and low-income families should not bear the burden of fiscal consolidation measures.

Taxing major corporations could be an important source of revenue after the pandemic. The idea of a global minimum corporate tax rate has been gaining traction, with Finance ministers from G7 countries recently reaching a historic accord backing a 15%-plus tax (59). This tax would discourage multinational companies from shifting profits from intangible sources (such as software or royalties on intellectual properties) to low-tax countries in an attempt to escape higher taxes in their home countries. The OECD estimates the tax would raise $50 to $80 billion per year globally (60), which, in the aftermath of a pandemic that eroded public finances everywhere, is especially and urgently needed.

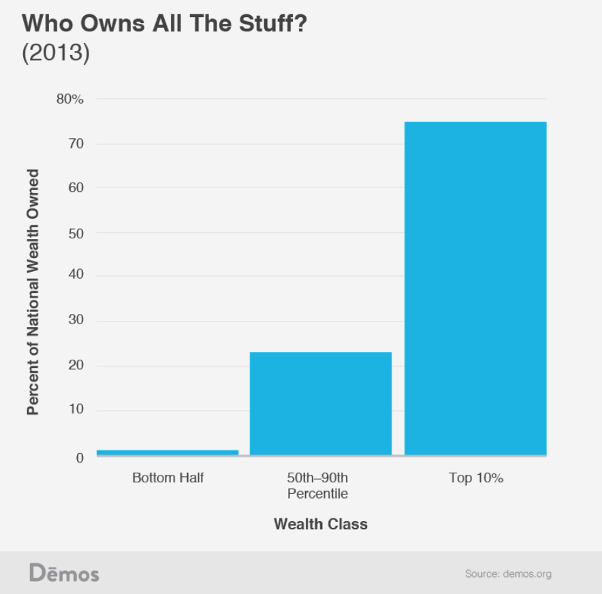

The IMF also suggested a temporary wealth tax to help cover the cost of pandemic relief (61). Although a politically contentious topic, there is increasing support for it in the developed world, with 64% of Americans on board with taxing the super wealthy (62). Wealth taxes could be a powerful instrument to target economic inequality, as wealth concentration is twice as great as income inequality (63). Economist Thomas Picketty has advocated for a global wealth tax to combat inequalities and encourage social mobility because wealth is self-reinforcing: wealthy individuals have more to invest in higher-yielding assets and access to investment advice. When the rate of return on capital surpasses the rate of economic growth, accumulated wealth will grow faster than wealth earned through labor, so wealth accumulation cannot be resolved without a tax (64). Opponents argue that it is difficult and costly to calculate an individual’s wealth and wealth can be shifted abroad into tax havens (65). However, the World Bank recently countered it is now more difficult for the ultrarich to transfer their wealth into tax shelters. BEPS measures (Base Erosion and Profit Shifting) are falling, and 125 countries are now members of the Inclusive Framework on BEPS. Just as with the global minimum corporate taxes, a global conjoined effort could create a sustainable system of wealth taxes that avoids evasion. (66).

The wealthiest individuals often accumulate their wealth through shares, real estate, and other assets. Long-term capital gains – the income earned through the sale of an asset held for more than a year – are taxed at a much lower rate than ordinary income earned through labor and are not taxed at all in some countries (67). To correct economic inequality, taxes should be shifted towards capital because the owners of capital are disproportionately the richest individuals (Chart 8 represents owners of capital in America).

- International Recovery

The economic recovery of low-income countries is going to be stymied by unequal access to vaccination, limited resources for social spending and high levels of public debt (68). The IMF projects these countries will need $200 billion dollars to step up their responses to the pandemic, and $250 billion extra to catch up with developed countries (69). Securing external financing from International Financial Institutions and developed countries is crucial. There have been numerous calls for an issuance of upwards of $500 billion in Special Drawing Rights (SDR) (70), and the IMF board of governors approved a $650 billion allocation in late August. SDRs are an international reserve asset created by the IMF to supplement its member countries’ official reserves and provide liquidity support in times of crisis (71). Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz highlights the importance of the provision of SDRs and adds they come with little to no cost to taxpayers in developed economies (54).

Countries with heavy debt burdens are especially vulnerable and less able to mobilize resources. The International Development Agency called for urgent action on debt and denounced advanced economies for not relieving the debt burden on developing countries, who were already under substantial strain before the pandemic hit (69). The G20 created the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), providing eligible low-income countries the possibility of requesting a temporary suspension of debt-service payments on their official bilateral creditors, and called on private creditors to participate in this initiative (72). However, the suspension period ends in December 2021 and many developing economies will need resources to fight the pandemic and subsequent crisis beyond that date, especially considering the much more limited access to vaccination they have been granted. More aggressive measures such as debt cancellation should be taken to give developing countries a fair chance at recovery.

References:

- Bhalla, Nita. “COVID-19: How Many People Lost Income Due to the Pandemic?” World Economic Forum, 6 May 2021, www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/05/how-many-people-experienced-a-lower-income-due-to-covid-19.

- International Labour Organization. World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2021. International Labour Office, 2021.

- “COVID-19 to Add as Many as 150 Million Extreme Poor by 2021.” World Bank, 7 Oct. 2020, www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/10/07/covid-19-to-add-as-many-as-150-million-extreme-poor-by-2021.

- International Labour Organization. “COVID-19 and the World of Work.” ILO Monitor, vol.7, 2021.

- Picchi, Aimee. “Billionaires Got 54% Richer during Pandemic, Sparking Calls for ‘Wealth Tax.’” CBS News, 1 Apr. 2021, www.cbsnews.com/news/billionaire-wealth-covid-pandemic-12-trillion-jeff-bezos-wealth-tax.

- BBC News. “‘Wealth Increase of 10 Men during Pandemic Could Buy Vaccines for All.’” BBC News, 25 Jan. 2021, www.bbc.com/news/world-55793575.

- Fontinelle, Amy. “Economic Inequality.” Investopedia, 28 May 2020, www.investopedia.com/economic-inequality-4845459.

- Kagan, Julia. “Income Definition.” Investopedia, 31 May 2021, www.investopedia.com/terms/i/income.asp.

- United Nations: Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World social report 2020: Inequality in a rapidly changing world (United Nations, Ed.). United Nations, 2020.

- Ranasinghe, Dhara. “Analysis: If Not Now, When? COVID-19 Spurs Global Push to Tackle Wealth Gap.” Reuters, 26 May 2021, www.reuters.com/business/if-not-now-when-covid-19-spurs-global-push-tackle-wealth-gap-2021-05-26.

- Partington, Richard. “Inequality: Is It Rising, and Can We Reverse It?” The Guardian, 9 Sept. 2019, www.theguardian.com/news/2019/sep/09/inequality-is-it-rising-and-can-we-reverse-it.

- Keeley, Brian. “Why is income inequality rising?”. Income Inequality: The Gap between Rich and Poor, OECD Publishing, 2015.

- Afonso, Helena et al. “Inequality Measurement”. Development Issues No. 2, UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2015.

- Chancel, Lucas. World Inequality Report 2018. World Inequality Lab, 2018.

- United Nations, World Social Report 2020: Inequality in a Rapidly Changing World. UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2020.

- Krauskopf, Lewis. “Cheaper Robots Could Replace More Factory Workers: Study.” Reuters, 10 Feb. 2015, www.reuters.com/article/us-manufacturers-robots-idUSKBN0LE00720150210.

- Acemoglu, Daron et al. Economics. Pearson, 2018.

- ILO, OECD, IMF and World Bank. Income Inequality and Labour Income Share in G20 Countries: Trends, Impacts and Causes. Prepared for the G20 Labour and Employment Ministers Meeting, 2015.

- Wei, Hongcen. The Effects of Financial Deregulation on Wage Inequality. The University of Chicago, 2021.

- Asen, Elke. “Corporate Tax Rates Around the World.” Tax Foundation, 9 Dec. 2020, taxfoundation.org/publications/corporate-tax-rates-around-the-world.

- Furceri, Davide et al. “Will COVID-19 Affect Inequality? Evidence from Past Pandemics”. IMF Working Papers, 2021.

- International Labour Organization. “COVID-19 Crisis and the Informal Economy: Immediate Responses and Policy Challenges”. ILO Brief, 5 May 2020, https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/employment-promotion/informal-economy/publications/WCMS_743623/lang–en/index.htm

- Webb, Aleksandra, et al. “Employment in the Informal Economy: Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, vol. 40, no. 9/10, 2020, pp. 1005–19.

- International Labour Organization. Women and Men in the Informal Economy. International Labour Office, 2018.

- Romei, Valentina. “How the Pandemic Is Worsening Inequality.” Financial Times, 31 Dec. 2020, www.ft.com/content/cd075d91-fafa-47c8-a295-85bbd7a36b50.

- Stiglitz, Joseph et al. “How the Economy Will Look After the Coronavirus Pandemic.” Foreign Policy, 6 Sept. 2020, foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/15/how-the-economy-will-look-after-the-coronavirus-pandemic.

- International Labour Organization. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Jobs and Incomes in G20 Economies. Prepared for the 3rd Employment Working Group (EWG) meeting under the Saudi G20 Presidency, 2020.

- Crutsinger, Martin. “Fed Warns High Asset Prices Could Make Investors Vulnerable.” ABC News, 6 May 2021, abcnews.go.com/US/wireStory/fed-warns-high-asset-prices-make-investors-vulnerable-77542339.

- Woods, Hiatt. “How Billionaires Saw Their Net Worth Increase by Half a Trillion Dollars during the Pandemic.” Business Insider, 2 Nov. 2020, www.businessinsider.com/billionaires-net-worth-increases-coronavirus-pandemic-2020-7?international=true&r=US&IR=T.

- PwC and UBS. “Riding the Storm: Market Turbulence Accelerates Diverging Fortunes”. Billionaires Insights, vol. 7, 2020.

- Autor, David and Elisabeth Reynolds. “The Nature of Work after the COVID Crisis: Too Few Low-Wage Jobs.” The Hamilton Project. Brookings, 2020.

- Ghosh, Iman. “How Has the Pandemic Affected America’s Small Businesses?” World Economic Forum, 5 May 2021, www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/05/america-united-states-covid-small-businesses-economics.

- Rose, Nancy L. “Will Competition Be Another COVID-19 Casualty?.” The Hamilton Project. Brookings, 2020.

- Autor, David et al. “The Fall of the Labor Share and the Rise of Superstar Firms”. Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 135, no. 2, 2020, pp. 645-709.

- Coy, Peter. “Remarks The Legacy of the Lost Year Will Be Devastating Inequality.” Bloomberg, 10 Mar. 2021, www.bloomberg.com/tosv2.html?vid=&uuid=0609c2b0-d90c-11eb-b783-2f8bfe27bb6b&url=L25ld3MvYXJ0aWNsZXMvMjAyMS0wMy0xMC9jb3ZpZC1wYW5kZW1pYy1tYWRlLXJhY2lhbC1pbmNvbWUtaW5lcXVhbGl0eS1tdWNoLXdvcnNl.

- United Nations. “Unequal Vaccine Distribution Self-Defeating, World Health Organization Chief Tells Economic and Social Council’s Special Ministerial Meetinget.” United Nations Meetings Coverage and Press Releases, 16 Apr. 2021, www.un.org/press/en/2021/ecosoc7039.doc.htm.

- Gaspar, Vitor et al. “Tailoring Government Support.” IMF Blog, 7 Apr. 2021, blogs.imf.org/2021/04/07/tailoring-government-support.

- International Monetary Fund. “Regional Economic Outlook for Sub-Saharan Africa”. Press Briefing, 2020.

- López, Humberto. “Latin America, the Pandemic and the Challenge of Building Better Instead of Going Back.”World Bank Blogs, 8 June 2020, blogs.worldbank.org/latinamerica/latin-america-pandemic-and-challenge-building-better-instead-going-back.

- Zeballos-Roig, Joseph. “The IMF Says Governments Should Consider New Wealth Taxes to Raise Cash from the Rich as Coronavirus Slams the Global Economy.” Business Insider, 21 Apr. 2020, www.businessinsider.com/governments-wealth-taxes-imf-new-source-revenue-coronavirus-economy-consider-2020-4?IR=T.

- Schwab, Klaus. “How to Sustainably Revive the Economy after COVID-19.” World Economic Forum, 12 Oct. 2020, www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/10/coronavirus-covid19-recovery-capitalism-environment-economics-equality.

- Berkhout et al. “The Inequality Virus: Bringing Together a World Torn Apart by Coronavirus through a Fair, Just and Sustainable Economy”, Oxfam Briefing Paper. Oxfam International, 2021.

- Zamora, Leah and Ben Phillips. “COVID-19 and Public Support for Radical Policies.” Center on International Cooperation, 15 June 2020, https://cic.nyu.edu/publications/covid-19-and-public-support-radical-policies

- Groundwork Collaborative. “Americans Seeking Further Economic Relief Amidst COVID-19 Pandemic.” Roosevelt Institute, 29 Apr. 2021, https://rooseveltinstitute.org/publications/americans-seeking-further-economic-relief-amidst-covid-19-pandemic/

- International Monetary Fund. Policy Tracker, 2021.

- Asaria, Miqdad, et al. “Pandemics Make Us More Averse to Inequality.” VoxEU CEPR Policy Portal, 15 Apr. 2021, voxeu.org/article/pandemics-make-us-more-averse-inequality.

- Wiwad, Dylan et al. “Recognizing the Impact of COVID-19 on the Poor Alters Attitudes Towards Poverty and Inequality.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 93, 2021.

- Arneson, Richard. “Egalitarianism.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 24 Apr. 2013, plato.stanford.edu/entries/egalitarianism.

- Lippert-Rasmussen, Kasper. “Justice and Bad Luck.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 28 Mar. 2018, plato.stanford.edu/entries/justice-bad-luck/#NeutLuckEqua.

- “Coronavirus (COVID-19): Work and Financial Support.” GOV.UK, 2020, www.gov.uk/coronavirus/worker-support.

- “Coronavirus Tax Relief and Economic Impact Payments | Internal Revenue Service.” IRS, 22 June 2021, www.irs.gov/coronavirus-tax-relief-and-economic-impact-payments.

- Ball, Laurence et al. “The Distributional Effects of Fiscal Consolidation.” IMF Working Papers, 2013.

- Furceri, Davide. “Fiscal Austerity Intensifies the Increase in Inequality After.” VoxEU CEPR, 3 June 2021, voxeu.org/article/fiscal-austerity-intensifies-increase-inequality-after-pandemics.

- Stiglitz, Joseph. “Conquering the Great Divide: COVID-19 and Global Inequality.” IMF F&D, 2020, www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2020/09/COVID19-and-global-inequality-joseph-stiglitz.htm.

- Boyle, Michael J. “Expansionary Policy Definition.” Investopedia, 21 Nov. 2020, www.investopedia.com/terms/e/expansionary_policy.asp.

- United Nations. Responding to COVID-19 and Recovering Better. UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2020.

- Lazar, Malerie, and Lisa Davenport. “Barriers to Health Care Access for Low Income Families: A Review of Literature.” Journal of Community Health Nursing, vol. 35,1, 2018, pp. 28-37.

- Dorn, Emma et al. “COVID-19 and Student Learning in the United States: The Hurt Could Last a Lifetime.” McKinsey & Company, 14 Dec. 2020, www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/covid-19-and-student-learning-in-the-united-states-the-hurt-could-last-a-lifetime.

- Thomas, Leigh, and David Lawder. “What Is a Global Minimum Tax and What Will It Mean?” Journal of Accountancy, 5 June 2021, www.journalofaccountancy.com/news/2021/jun/what-is-global-minimum-tax-g7.html.

- OECD. “Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Economic Impact Assessment: Inclusive Framework on BEPS”, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, 2020.

- Elliott, Larry. “IMF Calls for Wealth Tax to Help Cover Cost of Covid Pandemic.” The Guardian, 7 Apr. 2021, www.theguardian.com/business/2021/apr/07/imf-wealth-tax-cost-covid-pandemic-rich-poor.

- Schneider, Howard, and Chris Kahn. “Majority of Americans Favor Wealth Tax on Very Rich: Reuters/Ipsos Poll.” Reuters, 10 Jan. 2020, www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-election-inequality-poll/majority-of-americans-favor-wealth-tax-on-very-rich-reuters-ipsos-poll-idUSKBN1Z9141.

- Balestra, Carlotta and Richard Tonkin. “Inequalities in household wealth across OECD countries: Evidence from the OECD Wealth Distribution Database”. OECD Statistics Working Paper Series. OECD Statistics and Data Directorate, 2018.

- Piketty, Thomas, and Arthur Goldhammer. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Reprint, Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press, 2017.

- “Would a ‘Wealth Tax’ Help Combat Inequality? A Debate with Saez, Summers, and Mankiw.” YouTube, uploaded by Peterson Institute for International Economics, 18 Oct. 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=oUGpjpEGTfE&t=1200s.

- Brumby, Jim. “A Wealth Tax to Address Five Global Disruptions.” World Bank Blogs, 7 Jan. 2021, blogs.worldbank.org/governance/wealth-tax-address-five-global-disruptions.

- “Capital Gains Tax (CGT) Rates.” Tax Summaries PwC, 2021, taxsummaries.pwc.com/quick-charts/capital-gains-tax-cgt-rates.

- Chabert, Guillaume et al. “Funding the Recovery of Low-Income Countries After COVID.” IMF Blog, 5 Apr. 2021, blogs.imf.org/2021/04/05/funding-the-recovery-of-low-income-countries-after-covid.

- International Monetary Fund. “Macroeconomic Developments and Prospects in Low-Income Countries – 2021”. IMF Policy Paper, vol. 20, 2021.

- “Special Drawing Rights (SDR) Allocation Is a Unique Opportunity to Secure a Global Green, Inclusive COVID-19 Recovery.” United Nations Development Programme, 24 June 2021, www.undp.org/press-releases/special-drawing-rights-sdr-allocation-unique-opportunity-secure-global-green.

- “Special Drawing Rights (SDR).” IMF, 1 Aug. 2016, www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/Sheets/2016/08/01/14/51/Special-Drawing-Right-SDR.

- “Debt Service Suspension Initiative.” World Bank, 18 June 2021, www.worldbank.org/en/topic/debt/brief/covid-19-debt-service-suspension-initiative.

Image courtesy of The Economist